With many of our long-distance migrants already departed, this week was generally slow for the Lesser Slave Lake Bird Observatory (LSLBO) with one exception: after days of rain and high winds, the nice weather on September 20 provided this year’s busiest day in the nets with 231 captures as birds foraged to make up for lost time. Most of these captures were Myrtle Warblers which are one of the subjects of a current collaborative research project.

Last week we discussed the first part of this project coordinated by Environment and Climate Change Canada which involves collecting tail samples from aerial insectivores. The other part of this project focuses on several songbird species with multiple foraging strategies and habitat associations.

This Black-and-white Warbler was the first bird to get his tail sampled in 2022.

This Myrtle Warbler was one of the latest tails sampled this week.

A key habitat on the landscape for both our breeding and migratory birds is wetlands. These habitats offer a multitude of resources for birds through complex vegetation that provide many places to hide a nest or to hide while foraging the wetland’s bountiful food resources. Compared to other foods birds commonly eat, aquatic prey is often more nutritious and can help raise healthy babies with the best chances at survival.

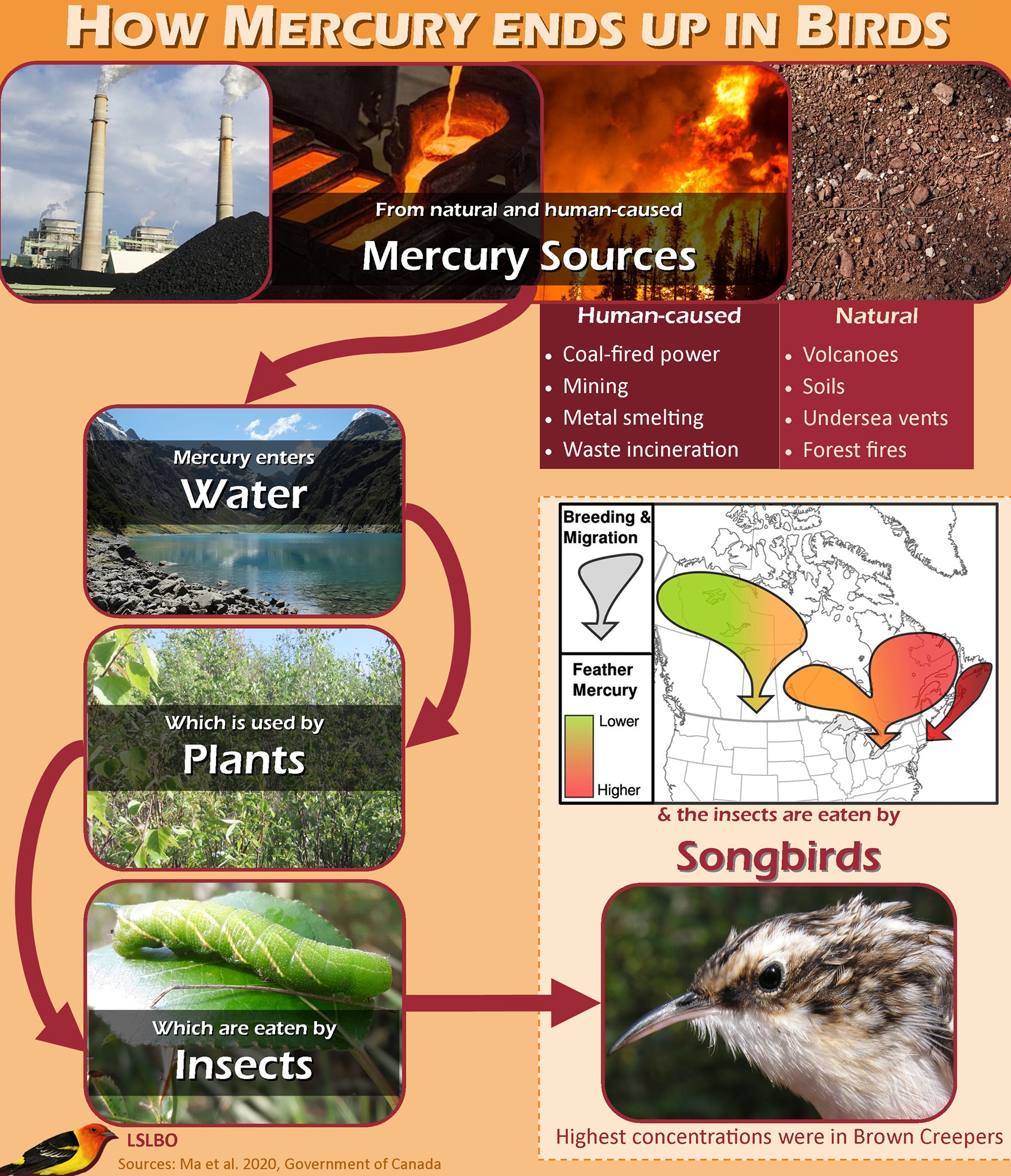

However, as flowing waters slow when they pass through wetlands, heavier particles can drop out and settle into the wetland’s soils. These particles can include heavy metal contaminants which can be taken up by plant roots. The plant can then be eaten by small aquatic organisms which can in turn be eaten by birds, moving contaminants up the food chain at each step. As birds eat more contaminated prey, these heavy metals accumulate in the birds’ tissues and have detrimental effects on their health and fitness, change singing behaviour, and harm their ability to have young and to migrate.

Though more nutritious food may be available for species that forage in wetlands, this same food may expose them to more contaminants than upland species. The full extent of this trade-off is poorly understood and may be revealed through a simple pluck of two tail feathers on a handful of individuals by this study since concentrations of both nutrients and heavy metals may be stored in feathers. Plucking does not impair the bird’s flight and regrowth of these feathers begins almost immediately.

A similar study published in 2020 which also used tail samples collected by Canadian Migration Monitoring Network stations, including the LSLBO, considered concentrations of a heavy metal, mercury. It found concentrations were highest in Eastern Canada, where mercury contaminants are more common. Although Canada’s mercury emissions have decreased by 90% since the 1970s, it persists in the environment and the consequences of the past’s lax regulations may continue to be felt for decades to come. As such, it is important that Canadians continue to prevent polluting our environments since the scale of pollution’s harm can be difficult to correct once the damage has been done.

By Robyn Perkins, LSLBO Bander-in-Charge